Is the museum the only way to revitalize post-mining sites? The case of Lercara Friddi, Sicily

Description

Lercara Friddi is a town in the Palermo hinterland, one of the farthest from the capital of the region (Sicily). Historically, it was an important mining center, the only one afferent to Palermo, through which sulfur was extracted. This small rural center, already existing, went through a phase of significant development thanks to the mine, around the first half of the nineteenth century. The economic importance of the site received the attention of many foreign entrepreneurs, first of all the Rose-Gardners (American and English), related to the more famous Whitaker family. Thanks to this kind of attention, Lercara Friddi developed considerably: economically but above all demographically, soon becoming a large center, unique in the rural landscape between Palermo, Agrigento and Caltanissetta. The extracted and treated sulfur was sent to Palermo, thanks to a railway network built ad hoc around 1870, in operation until 2015-2017, although with a different function.

The demographic boom and the new interest in the Lercara Friddi’s area did not, however, mean generalized welfare nor social progress: not only for the conditions in which the miners worked, but also for the extreme fragility of the entire mining system: already at the beginning of the 20th century, the extraction and processing of sulfur entered a crisis, as it was no longer particularly relevant.

Lercara Friddi was also the first center to be documented journalistically: Jessie White-Mario documented, precisely in Lercara, for the first time, what the mines were and what the cost was to pay in terms of exploiting labor in inhumane conditions, especially female and juvenile.

Nonetheless, the extraction continued with difficulty until the third quarter of the 1900s, although accompanied by numerous strikes, many human losses and an overall social and environmental impoverishment (the prolonged strike of the miners in 1951 received a particular media echo).

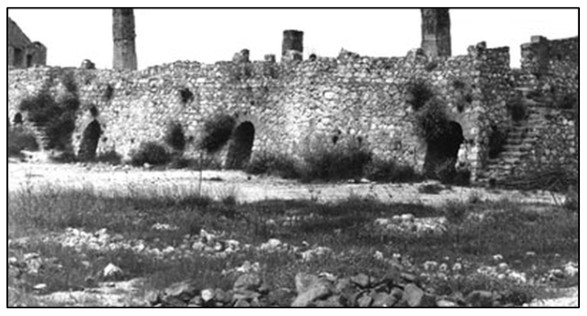

What remains of this modern mining complex today?

First of all, an overall impoverishment of the landscape and natural heritage: according to one of the most recent reports of the Regional Department of Water and Waste, there are at least five extraction sites in the Lercara area (belonging to five different concessions) that need reclamation and restructuring.

The constant mining activity, for more than a century, has caused constant emissions of sulfur dioxide: it was not only the miners who paid the price, but also the landscape in its entirety. From a cultural, monumental, architectural point of view, what remains? According to Luciano Marino, mayor of Lercara Friddi, very little indeed.

An old "Gill" oven, the ruins of an old electrical substation, part of an old mining well, a few sheds and little else.

Nonetheless, it has been a long time since Lercara Friddi and, more generally, the extraction of Sicilian sulfur, have been considered a perfect and dramatic example of industrial archeology.

What caused all the artifacts to be destroyed?

First of all, illegal building: especially during the 1970s, much of the rural landscape of Lercara was, like many other Italian realities, strongly redesigned by uncontrolled urban expansions. This has caused the demolition of many kilns and sites belonging to the old sulfur mine.

Furthermore, even today, many post-mining sites belong to private individuals. Nevertheless, the local administration has repeatedly said that it is interested in the construction of a landscape-naturalistic route, capable of encouraging internal and foreign cultural tourism, as happens in many European countries.

The Lercara Friddi mine is in fact even more important: most of the post-mining sites coincide with the ancient area of the archaeological center. The goal and ambition would be to build an entire path of discovery of the Sicilian hinterland, from antiquity to the post-industrial examples of the late modern age.

Aigae, the Italian Association of Environmental and Hiking Guides, has already carried out numerous inspections and has designed possible itineraries for visits, both for the archaeological and for the post-industrial part, including numerous wells, caves and ancient mining workplaces.

Nonetheless, all of this remains more of an intention, first of all lacking adequate infrastructures and sufficient funds.

What is the role of the museum?

Given the intentions of the current municipal administration of Lercara, it is clear that the mine museum represents a starting point, not a fallback.

Already in 2010 the Sicily Region established the Archaeological-Industrial Park Service and the Lercara Mine Museum, although not really operational: neither studies nor preliminary works were ever completed to really start this ambitious cultural initiative, which it would be the only one of its kind in Sicily.

In addition, a regional resolution of 2013 definitively superseded the birth of the Archaeological Park, together with many others in the region.

However, recently and precisely in 2021 there has been a renewed interest in the mining heritage of Lercara Friddi: this time, solely focused on the preparation and strengthening of the Villa Rose Museum.

The initiative is the result of a collaboration between public and private, with funding of EUR 367,548.78, derived from the 2014-2020 Development and Cohesion Fund. The goal is to complete the works within the year.

The museum is housed in Villa Rose (or Villa Lisetta), the residence of the Rose-

Gardner entrepreneurs who started the mining boom in Lercara.

What is this project for?

To an overall revitalization of the museum spaces, never really completed: archive, library, display cases, conference room. New furnishings for the exhibition rooms dedicated to the processing of sulfur, multimedia elements, models, dioramas. The goal is to start from the bottom, in order to to recover the historical memory linked to the productive activities of Sicily, to make the Sicilian inland and rural areas more attractive, also as a destination for educational visits, according to the words of the current Councilor for Culture of the Sicily Region.

Sulfur was, together with agriculture, one of the few and profitable areas of production in the region until at least the 1950s, but also one of the most humanly dramatic brackets, marked by deaths at work, inhuman living conditions and destruction of the environmental and landscape asset.

The museum is housed in Villa Rose (or Villa Lisetta), the residence of the Rose-Gardner entrepreneurs who started the mining boom in Lercara.

What was the sulfur used for?

As a pseudo-popular medicine, first of all. But its primary purpose was of a war nature: sulfur was mixed with saltpetre and coal, creating gunpowder: a war explosive used until the end of the 19th century.

Another important use is for the packaging of caustic soda.

Even today it is possible to see the ancient mining plots: Colle Madore, Colle Friddi, Colle Croce, Colle Serio, arranged in a square. The Villa Rose Mine Museum can be partially visited, but it will still need numerous interventions before becoming an educational and cultural center truly open to the public.